By now those of you who have read a few of my reviews are aware that I’m a huge Marvel fan, and love (or mostly love) every new MCU film that’s released. I also (and this should come as no surprise) try to attend the midnight showings, so that I can be among the first to see the film. This was the case with Captain America: Civil War, as the marketing strategy behind the film sold it not just as the third film in the Captain America trilogy, but also as an Avengers 2.5, if only because there were so many Avengers in this film. And so, instead of just doing a straight review of Civil War, I’ve instead opted to do a think-piece, if only for the reason that yes, whilst I enjoyed this film very much, saw it on three separate occasions in the cinema, and have had multiple repeat viewings whilst at home, I have to admit that there are some issues with it. And these issues, unfortunately, are unavoidable, to the point where when I walked out of the cinema the first time, I was actually a little disappointed alongside being happy at having enjoyed the final entry for Cap.

One of people’s main gripes with the film side of the MCU is its distinct lack of properly fleshed out villains. Apart from Loki, is there one villain who you can easily name off the top of your head who left a lasting and interesting impact? Perhaps you could name the Mandarin – or Trevor Slattery – on account that that reveal and twist seriously annoyed a lot of fans and is one of the main reasons why many people dislike Iron Man 3. Personally, I thought it was the best out of the three films, and the twist – while a tad disappointing and jarring during the initial viewing in the cinema – ended up being quite a gutsy move on Marvel’s part after I stopped to think about it. Or you could name Ronan the Barbarian from Guardians of the Galaxy on account that he’s a Kree and defies Thanos (which is a bold move, even if so far all we’ve seen Thanos do is sit and grin evilly, or steal the Infinity Gauntlet from somewhere in the mid-credits scene in Avengers: Age of Ultron and mutter the words: ‘Fine; I’ll do it myself!’ And other than Thanos (who is expected to kick some serious ass and be an actual threat to Earth’s Mightiest Heroes in this summer’s Avengers: Infinity War, which has now been moved up to April 27th on a worldwide scale for various reasons), the chances are, you can’t recall many villains.

The reason behind this is that MCU movies usually focus on the titular hero of the film in question: all three Iron Man films focus on Iron Man; the same for both Thor and Captain America (although in the case of Thor, the villain is Loki, but my point still stands, and in the case of Captain America: The Winter Soldier, the villain is Hydra and the ‘villain’ is Bucky Barnes/the Winter Soldier (Sebastian Stan), but even so); Doctor Strange, Guardians of the Galaxy, Ant-Man, and The Incredible Hulk (yes, I’m counting it) are all origin stories of sorts that deal with each respective hero (or group of heroes) coming to terms with their powers. This means that a lot of screen time is therefore devoted to Tony Stark/Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.), Thor, Steve Rogers/Captain America (Chris Evans), Bruce Banner/Hulk, Dr. Stephen Strange, Scott Lang/Ant-Man (Paul Rudd), and Peter Quill/Star Lord, Gamora, Drax, Groot, and Rocket Raccoon. And because these films have to be a certain length to keep audiences entertained (the shortest so far is The Incredible Hulk, with a runtime of 112 minutes, whilst the longest so far is the subject of this review, at 146 minutes), there is only so much that screenwriters can be expected to fit in. Yet whichever way we look at it, the villains of the MCU, by and large, end up getting snubbed for some reason or other.

Granted, this is not the TV division of the MCU, be it Marvel’s flagship television show Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., or any of the Netflix Marvel shows (such as Daredevil, Jessica Jones, or The Punisher), where the villains are allowed room to breathe, simply because TV shows span a longer runtime. With AoS, the main villain is Hydra, but they work around this and incorporate other antagonists for our main characters. In regards to Daredevil – and perhaps even more prominently, Jessica Jones – we’re treated to villains who are so compelling that you can’t help but like them in a morally twisted sort of way. Both the Kingpin (Daredevil) and Kilgrave (Jessica Jones) are played with fantastic aplomb and glee by Vincent D’Onofrio and David Tennant, respectively. These are villains that are just as fleshed out as the heroes; they are given the stories worthy of their status, and they make for a more engaging viewing. This is true for The Punisher, to an extent, in that the villain has a backstory that’s both relevant to the story, but also damaging to our antihero, Frank Castle. Unfortunately, this isn’t necessarily the case with MCU films, and the result is usually something that comes off as a bit half-arsed.

Now how does my critique of Marvel’s villains play into Civil War? That’s pretty easy: the ‘main’ antagonist (and I’ve put quotation marks around ‘main’ because it’s actually quite a complex film, but I’ll dive into that in more detail in a bit) is Baron Zemo (Daniel Brühl), who has a plan to try and tear the Avengers down from within, because of the events of Age of Ultron (which is something else that I’ll explore in much more depth in regards to how it shapes this film). If you just watch Civil War, and not think too much about Zemo’s overall plan or actions in how he goes about implementing it, you’ll probably not even realise just how convoluted the plan is, or how heavily it relies on luck and certain people being in certain places at certain times. Yet if you do stop to think about it, Zemo’s plan is not only crazy, but so farfetched and so improbable in the fact that it actually ends up working, that you’ll probably be scratching your head for a long time. It’s something that’s highlighted in minute detail by Honest Trailers (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BZ3VQkK6Upo), and if you read each of the points, you’ll begin to understand just how insane the plan is. And due to the fact that there are so many characters within Civil War anyway, you have to stop and wonder why Zemo is even in the film.

How, then, can this be fixed? Well, the first thing is to try and make a more compelling villain. In terms of Zemo, was it necessary to have him in the film? This is a difficult question, as it’s one that’s almost a two-pronged answer, covering both the ‘yes’ and the ‘no’ aspects. The reason he could perhaps have been left out of Civil War was that there were so many characters in the film already, that his presence merely added to what was arguably an already inflated cast. And considering how he was meant to be the ‘main’ villain, he once again fell into the trap that Marvel have put themselves in by not being a particularly great bad guy. And just to make matters worse, he isn’t the only antagonist of the movie, either. The opening ten minutes of Civil War see Cap and his team (made up of Sam Wilson/Falcon (Anthony Mackie), Natasha Romanoff/Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson), and Wanda Maximoff/Scarlet Witch (Elizabeth Olsen)) taking down Brock Rumlow/Crossbones (Frank Grillo), which culminates in him blowing himself up, even though he was an already-established antagonist due to being part of Hydra in The Winter Soldier. This needed to happen in order for the Sokovia Accords to come into play, and for the rift between the Avengers to manifest.

At the same time, Zemo did need to be in Civil War, if only to showcase that there are consequences in Marvel films. This is perhaps the biggest ‘offender’ – if it can be called as such – that I hear whenever people have issues with the MCU. It’s the fact that there aren’t any consequences. For example, in AoU, Tony builds Ultron, Ultron tries to destroy the world, the Avengers clean up their own mess. Incidentally, yes, they do destroy a city by dropping it out of the sky, but they take great strides to try and save all the civilians first. Afterwards, they all go home (or in Thor’s case, goes in search of the Infinity Stones), and that appears to be that, with no lasting consequences. Except, in Civil War, there are consequences that spill over from AoU, and that’s one of the reasons why this film was sold as Avengers 2.5 as well as Cap 3. Due to the Avenger’s trouble with Ultron, Zemo lost his entire family, and that’s his impetus for destroying the Avengers. It’s a pretty solid reason for wanting to go up against them, but he knows that he is ordinary, knows that he is therefore limited, and that is why he wants them to fight each other, as he can’t do it himself. He doesn’t have a suit of armour, and has no super serum to make him into a super soldier.

Herein lies the tricky bit, though, and perhaps the reason why Civil War felt overly crowded. Yes, Crossbones needed to be in it in order to effectively create the Sokovia Accords (or his actions, in any case), and it also makes sense as he was a minor antagonist in Cap 2, so him being in Cap 3 was at least realistic – he wasn’t just thrown into the mix for the sake of it. However, the Sokovia Accords become the thing that Tony and Steve clashed over, and the reason why the Avengers form sides in the first place. This then negates the reason for having a second ‘main’ antagonist, as it were, and so Zemo’s place within the movie feels a little left-field. All he really does is introduce Bucky back into the fold, and pave the way for the third-act fight scene between Tony, and Steve and Bucky, while showing the viewer that there was a fallout and consequences from the events of AoU. Therefore, Zemo’s place within Civil War shows not only how the MCU is one complete storyline, but also that the films compliment each other and have lasting effects past the credits rolling. This is something that has never really been done before in cinema history, and this form of storytelling is much more common in a TV series such as AoS.

This long-form storytelling is something that casual moviegoers will not necessarily be accustomed to unless they’re committed to watching a 22-episode show on TV, which gives time for all the characters – both protagonist and antagonist – to breathe. And the reason I’ve compared it to something such as AoS – aside from the fact that it’s a Marvel property – is because the MCU, as it stands with Phase One, Two, and Three, is made up (or will be as of next year) of 22 films. Yes, granted, they are 22 films about a variety of different characters, all of whom have their own respective villains, but there’s a reason it’s called the Marvel Cinematic Universe: because they’re all linked, and there’s a lot of crossover. And so if we bear that in mind, we can safely assume that even if there are no consequences in one film by the time the credits roll, that doesn’t mean that there won’t be some repercussions by the time the next film comes out that then explains the consequences of a previous film. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a big consequence; it can be something such as Rumlow becoming Crossbones after he gets half-crushed by a building at the end of The Winter Soldier. But the fact that there are at least some consequences is something of a comfort. This is all well and good, but it doesn’t explain Marvel’s villain problem.

The thing about Civil War that makes it stand out from all the other MCU films that have come before it is the fact that it could have worked without an actual villain. Not only would this have solved the ‘problem’ (for this film, at least), but it would have made the movie a bit less crowded. I’m pretty sure that screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely could have worked Bucky into the story without the need for Zemo, too. Or, if they thought that Zemo was absolutely necessary (and to a certain extent he was), then it could have been the first issue that the Avengers had to tackle that they end up disagreeing over. This would have then exacerbated Tony and Steve’s argument over the Accords, and the Civil War between the Avengers would still have happened anyway. And seeing as I’ve just come up with an alternative as I’ve sat here writing this, it proves that it wasn’t too difficult at all. I think part of the reason why something such as what I proposed wasn’t used was because the creative team instead wanted to focus on the actual argument that ended up splitting the Avengers. And while this is predominately a think-piece in terms of Civil War’s most glaring issues, I have to say that both Markus and McFeely did do a great job on that front.

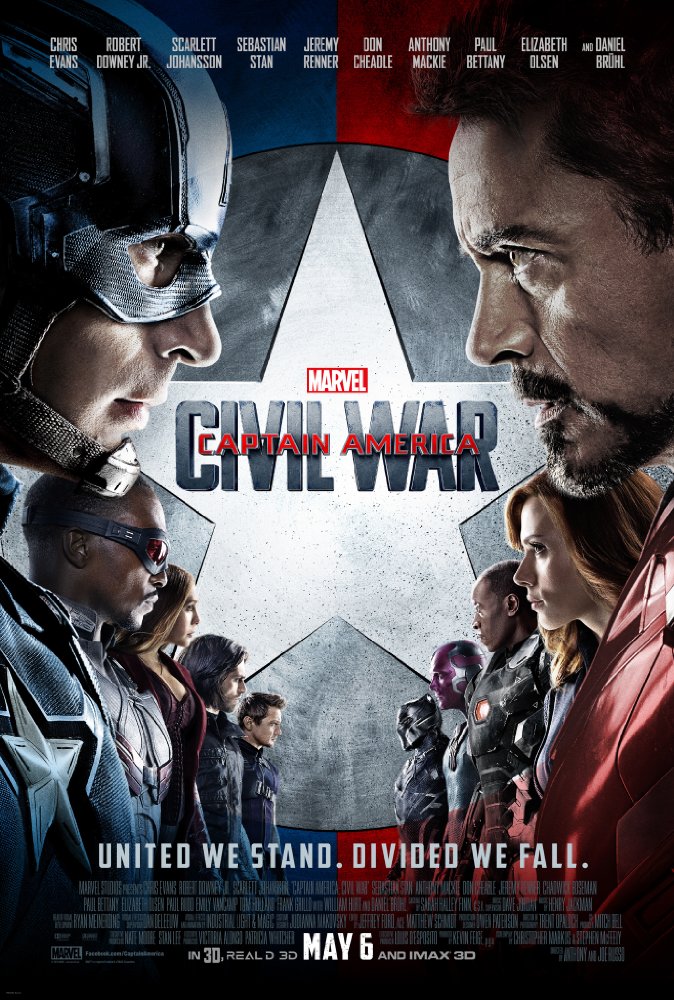

Civil War‘s ‘villain’ problem allows me to segue perfectly into my next point, and this is what the film actually managed to do extremely well. From a marketing standpoint, before the audience even stepped into the auditorium, you knew that there were two sides to this battle. There was Tony’s side, and there was Steve’s side. You knew that there were going to be two Teams: Team Captain America, and Team Iron Man. ‘Which side?’ and ‘Time to pick a side’ were both phrases that circulated around the marketing of the film. Yes, it was Cap’s movie, but at the same time, Tony’s role was far more than just a glorified cameo. Both sides had arguments that were valid, and both had their issues. For Steve, he did not want to sign the Accords, as he believed that government oversight was a bad idea, having already experienced it and then subsequently defeated it in the events of The Winter Soldier. He thought that saving the world was enough, and that governments should not interfere and just let them get on with it. Of course, without the events of Cap 2, his reasoning in the third film would not have made a lot of sense, and so therefore you can see the consequences of one film bleeding over into another.

You would think, because this is predominately Captain America’s film, that Cap is therefore the good guy, and Iron Man the bad guy, on the sole basis that he opposes Steve’s point of view. Yet that is not the case: Tony believes that government oversight is the way forward, and while this largely goes against Stark’s usually flippant attitude toward everything in life that isn’t about himself, it can be attributed to a sort of character development. The reason for this is because he gets confronted by a distraught woman called Miriam (played by Alfre Woodard, who also plays Mariah Dillard in Netflix’s Luke Cage, but that’s an altogether different issue that I won’t get into) who blames Tony – and the rest of the Avengers – for the death of her son, as he was in Sokovia at the same time as the events of AoU. Once more, this little – seemingly incongruous – scene demonstrates that there were consequences from the last Avengers film. This spurs Tony to decide to agree to the Accords, which ultimately leads to him and Steve tearing the Avengers apart. Yet due to the writing by Markus and McFeely, you’re able to not just see both sides of the argument, but also there is no obvious ‘right’ side. Simultaneously, there is no ‘wrong’ side, which proves my point about why this film did not necessarily need a villain.

And this is perhaps why no ‘main’ antagonist was necessary, as we still got the best adapted comic-book-to-big-screen superhero-on-superhero fight that we have ever seen. Even though I saw this film three times in the cinema, I’m disappointed to say that I never actually saw it in IMAX, as that scene was shot entirely using IMAX cameras, and was meant to be seen on the biggest screen possible. It’s true that it’s only fifteen minutes or so out of 146 in total, but those fifteen are completely worth it. The airport fight scene will go down as one of the most memorable superhero fights in cinematic history. Yes, it’s nowhere near the number in the comic books, but ignoring that, it is still one hell of a sequence, with heroes fighting on multiple fronts, switching between opponents, and keeping the audience entertained. There was also the right level of banter, something that can be hard to balance sometimes, especially in action sequences. Most of that banter came from Peter Parker/Spider-Man (Tom Holland), as his first appearance in the MCU after Marvel orchestrated a deal with Sony (which probably wasn’t helped by the bad reception of The Amazing Spider-Man 2, or the hack on Sony which led to an avalanche of leaks). Initially I wasn’t completely convinced by the casting of Holland, but his debut performance here was spot on, and put any worries and reservations I had to rest.

The other debut character in this film was T’Challa/Black Panther (Chadwick Boseman). Considering that by this point we’d already had six origin stories, one of which was a reboot of the 2003 film Hulk, it was nice to see them put Black Panther into an already-established character’s film, much like they did with Black Widow in Iron Man 2, Clint Barton/Hawkeye (Jeremy Renner) in Thor, and both Scarlet Witch and Vision (Paul Bettany) in AoU. We already knew that we’d be getting a Black Panther film in 2018, and that Spider-Man was getting his third reboot in fifteen years, so it was refreshing to see the characters introduced this way, instead. And as with the case of Spider-Man, it was a miniature fist-pump moment when Tony shut down Peter’s explanation of how he became Spider-Man. If ever there’s a comic book superhero who’s had one too many origin stories, it’s Spider-Man. Yet that’s not the case with Black Panther, and so his introduction into the MCU via Civil War was a two-pronged victory. For starters, it allowed the audience – both Marvel fans and general moviegoers – to see a Marvel character who perhaps wasn’t that well known. Secondly, it was prudent to put Black Panther in the opening Phase Three film, as he couldn’t have starred in any of the following Phase Three films as it wouldn’t have made a whole lot of sense, story-wise. Maybe it added to the character count, but this is one character whom I’ll happily defend endlessly.

What I won’t defend endlessly, though, is the lack of consequences. Yes, I mentioned above how the MCU is the first cinematic universe that is doing a sort of long-form storytelling in a similar vein to that of a 22-episode TV series, but that doesn’t mean that there can’t be actual consequences within the film itself. During the airport fight scene, both Black Widow and Hawkeye fight (and it’s perhaps the only bit of banter that I’m not best pleased with, but we’ll let that slide), and Wanda scolds Clint, telling him: ‘You’re pulling your punches.’ And if that’s not an unintentional self-fulfilling prophecy, then I’m not sure what is. Because the fact of the matter is, Marvel do have a tendency to do just that: pull their punches. The reason behind it is no fault on the part of screenwriters; more its the actor’s contractual obligations, in that they’ve got to star in a certain number of films, as per their contract. Due to this, it means that they can’t kill any characters off, but then again, when the actors in question are raking in as much money as they are doing for the studio, it’s not as if they’re going to kill characters off – especially not people such as Downey Jr. So that’s a bold statement, and anyone who has read the Civil War comics will know who dies at the end. If Marvel had decided to go down that route, that would have been a bold move.

But that’s not to say that they couldn’t have killed off a minor character. James ‘Rhodey’ Rhodes/War Machine (Don Cheadle) for example. It wouldn’t have been as groundbreaking as killing off either Iron Man or the titular character of the movie, but considering how they kind of paralyse him from the waist down, it did feel like a huge cop-out, and one that annoyed me greatly. If you’re going to injure a character and have them fall in such a way like that, and if you want actual consequences within the film that don’t involve the audience having to wait for a future film to find out if there are any long-lasting consequences, then this is the way to go. And I say long-lasting, because even after the climactic battle between Tony, Steve and Bucky, where one loses his shield and the other his arm, the end of the film still has to be tied up in a bow and ribbon, with a nice friendly little message and a burner phone sent to Stark from Cap. I understand how it would have been perhaps a controversial move to pull, ending it without our heroes ‘kind of’ making up, but it would have meant that Marvel planted themselves in the ground and gave out a big announcement, much like they did with TWS. The way the film ended is perhaps what led to my initial disappointment. Captain America: Civil War was a great film and a great start off for Phase Three (arguably much better than the start of Phase Two), but it’s also one that could have been so much stronger. For now, it is what it is, and we’ll have have to wait and see if Marvel continue their ‘consequences holdover’ when Avengers: Infinity War hits cinemas worldwide in two months’ time.

10 thoughts on “Review/Think-piece: Captain America: Civil War”